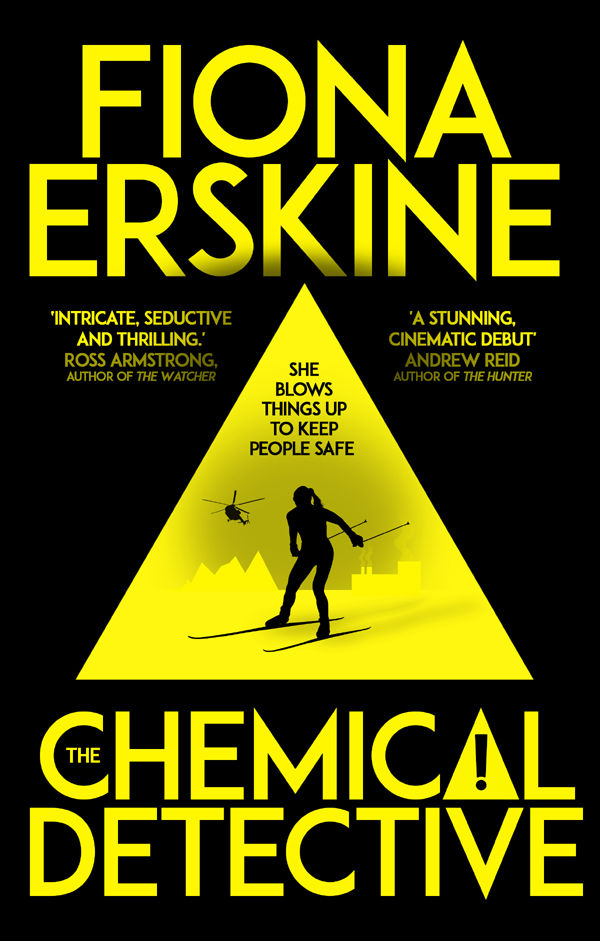

THE CHEMICAL DETECTIVE by Fiona Erskine is published by Point Blank, an imprint of Oneworld, in hardback on 4 April (see review on Goodreads)

I’m privileged to be able to interview Fiona Erskine, author of the brilliant new thriller The Chemical Detective. Back in September 2017, OneWorld announced that it had signed up for two ‘chemical detective’ novels, featuring the chemical engineer Dr Jaq Silver by Fiona, who is both a friend and a fellow Writers’ Workshop Self-Edit course graduate. The first of these is to be published imminently, and for intelligently explosive excitement, The Chemical Detective will not disappoint. Welcome Fiona…

– Can you first tell us something about you as a writer? When did you first get the urge to write a novel, and how did The Chemical Detective come into being?

“I’ve never wanted to be a writer, I’ve always enjoyed doing engineering. But when a dream job turned sour, writing became an escape. I was travelling and working far from home for long periods of time so I put pen to paper to try and make sense of what was happening.”

– Dr Jaq Silver is a fantastic central character. Did she come to you fully formed or did it take a lot of work to find your way into her head?

“She arrived fully formed! Jaq is both the easiest to write and the most difficult to write well. In early drafts I just follow where she leads. But when I’m editing, I struggle to share her reactions, emotions and thought processes with the reader. I know her so well, it’s hard to step back and be analytical.”

– One of the aspects of The Chemical Detective I enjoyed most was the way real science was woven into the plot and really drove it. How important was it to you that the basis of the plot concerned chemical engineering, and for Jaq, as a chemical engineer, to actually use her professional knowledge to solve the central mystery and tackle the villains of the piece?

“I didn’t really consider it; it was always the main driver for me. A friend gave me Primo Levi’s The Periodic Table to read when I was a student, and it was a revelation. Levi conveys the excitement and mystery of chemistry, the problem-solving and detective work essential to real life manufacturing and he does it in a way that is accessible to anyone. I am fascinated by how the modern world works and my drive has always been to wrap the science in a story that holds the attention of a non-specialist reader.”

– Did you have to fight to get the science this real and front-and-centre or were your agent, editor and publisher on the same page?

“I have been incredibly lucky. Juliet Mushens (my agent) asked me to cut the word count – and so some of the science stuff had to go – but that was to make the book appeal to as many publishers as possible. Once the deal was signed, Jenny Parrott (my editor at Oneworld) encouraged me to put the science back in. And develop that strand even further.”

– An aspect of The Chemical Detective that grounds it so well in the real world is the everyday condescension, casual sexism, and out-and-out misogyny that Jaq faces for just wanting to do her job. Is this something you wanted to highlight in the field? Is it something you’d like readers to reflect on even as they’re enjoying the adventure?

“Revenge is a dish best served cold. In conjuring up Frank Good, I was reacting to a particularly toxic management style, which wasn’t just misogynist, but misanthropic: many good men suffered as well. The first time I had direct dealings with a corporate psychopath, I didn’t last long,

“When I first started work in Scotland, I was an oddity. I was the only female engineer in a large fertiliser factory, but I drove a motorbike, drank pints of bitter (even at 6am after a night shift) and avoided discussing my personal life. Any sexism I encountered was completely overt and often veiled as protective concern. People would express their misgivings openly and you could usually work to change their minds. Or ignore them.

“When I moved from ICI in Scotland to work in Portugal, half the engineers were female. Men did military service and women had brief maternity leave before returning to work and most professional couples had family or domestic help at home – any gender disadvantage sort of balanced out.

“After I moved back to England, I worked for my first female boss in Cumbria, another chemical engineer, and she was (is) fantastic. Frances used to make cakes for the nightshift, and no-one thought any the less of her because she was really, really good at her job. I began to relax a little and be more open, more myself, at work.

“Engineers are, by and large, rather nice, cerebral people. The trouble comes when you get higher up in an organisation and encounter ruthless bastards like the Frank Goods of this world. I am a lot less forgiving of those who have all the benefits of further education and exposure to the wider world and yet still behave like utter pillocks.”

– The Spider is an absolutely bone-chilling opponent. Without giving too much away, can you say how you came up with him?

“In early drafts, The Spider had a much smaller role. I got some professional editing advice from the wonderful Kate Foster, and she felt that Pauk Polzin was too good a character to waste. As I was re-writing he just took over. You don’t argue with the Spider.”

– Because of the gender issues that a woman in what’s perhaps still perceived as a ‘man’s world’ can face, it makes sense that the people Jaq squares off against are principally men – in a sense it’s attitudes that she’s fighting as well as a criminal underworld. Can you see Jaq facing a female antagonist in future? Would you enjoy writing a female villain?

“Spoiler alert – Lots of female baddies in the next book! But you’re right, I can vent my spleen more easily through male characters it adds another dimension to a conflict that is so close to my heart.

– The locations in the novel are fabulously realised. There’s an almost Bond-film travelogue feel to the narrative, with everything from Teesside to the Slovenian Alps, but everything is convincingly painted. I can imagine that these are mostly, if not all, places you’ve visited in your work as a chemical engineer. When you got to go to exotic (and less exotic) locations were you thinking ‘this would be a great place for my character to go?’ or did you fit the locales to the action afterwards?

“I have visited most of the locations, but I don’t need to visit a place to write about it. (See Chornobyl question below).

“Work travel tends to revolve around industrial hubs, places most tourists avoid. I find them fascinating and have benefited hugely from the generosity of local colleagues happy to show me around and answer my endless questions.

“By contrast, family holidays have always been outdoor adventures. If I hadn’t injured myself skiing, I might never have found the time to complete the first draft of a novel. We swam the lakes of Slovenia one summer; Slovenia is a stunningly beautiful country and became the perfect setting for fictional Kranjskabel.

“The wonderful thing about travel is that it gives you new eyes to view the familiar. I dislike cars but I love the process of public travel, the trains and the planes, the stations and airports, striking up random conversations or just watching and listening. I love the absence of guilt – I am trapped for the journey and not obliged to do anything else for the duration; it’s my time. I relish the contrast of writing in locations that are completely different from those in the story. I wrote snow scenes while sweltering in 45 degree heat in India. I wrote hot, humid tunnel scenes in wide-open, windswept Shetland.”

– Which were your favourite locations to write about? What about them really spoke to you?

“I think there’s a reverse correlation. The more beautiful the place, the harder it is to find something new to say about it. With the open furnaces and mines in Baotou, Inner Mongolia – the problem with descriptive writing is only where to stop.”

– Chernobyl/Chornobyl and the associated town of Pripyat was a really powerful and poignant presence in the novel. How did you go about bringing such a notorious place into the narrative? You’ve written non-fiction works on the disaster as well – what did looking at it in a fictional context bring that you couldn’t do with more academic work?

“Isn’t it strange? Perversely, I have my fiction to thank for my non-fiction publications. The writer Jackie Buxton – we met on a self-edit your novel course – gave me a huge amount of help early on. My diatribes about process safety were getting in the way of the story and she suggested I wrote separate technical articles, aimed at my peers, with everything I wanted to say. I did and as a result I’ve had several articles published. Once I’d got that out of my system, I was better able to control the flow of information in the story so that it remained the central spine but didn’t overwhelm.

“I did a lot of research, read every serious book on the subject of the 1986 accident, but didn’t visit Chornobyl in person until after The Chemical Detective was at proof stage. And I had very little to correct, only a few lines set in Kiev.”

– Can you tell us what’s next for Jaq? When might we get to see her next adventure?

“Ooh, so glad you asked.

“Jaq is off to China to track down a vanishing factory with the help of a troupe of male strippers.”

THE CHEMICAL DETECTIVE by Fiona Erskine is published by Point Blank, an imprint of Oneworld, in hardback on 4 April